This story was originally published in the 2019 Fall edition of Upper Delaware Magazine.

Folk music is enigmatic: regional yet universal, artistic but utilitarian, belonging to no one and …

Stay informed about your community and support local independent journalism.

Subscribe to The River Reporter today. click here

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Listen while you read: Owen Walsh performs a rendition of "Jam on Gerry's Rocks."

This story was published in the fall 2019 edition of Upper Delaware Magazine.

Folk music is enigmatic: regional yet universal, artistic but utilitarian, belonging to no one and everyone, telling a story that isn’t over yet. Defining a folk song can be like trying to catch a fish with your bare hands—just when you think you’ve got a grasp, it slips away.

Like tall tales, lores and legends, the stories portrayed through folk songs can be treasure troves for historians trying to understand bygone culture, beliefs and values. But the very nature of the style—preserved orally and aurally but rarely transcribed—can yield more questions than answers.

Local historian Mary Curtis faced this very problem 40 years ago when she sought to compile the folk music of the Upper Delaware Region, so that it could be performed in a series of programs she was curating with the Delaware Valley Arts Alliance and National Park Service, called “Stories and Songs of the Raftsmen.”

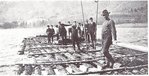

Its location on the Delaware and plentiful hills of hardwood trees allowed the Catskills to become home to a thriving timber industry in 1760. Many laborers came to the region to fell timber and build rafts during the winter and, in spring, float them down the river toward bigger cities. Raftsmen made up a sizable chunk of the population during these years. As many as 1,000 could have been found spending the night in Narrowsburg during at the industry’s peak, according to the Sullivan County Historical Society.

As raftsmen moved timber down the river, they spread their culture throughout the towns and hamlets, becoming another ingredient in the flavor of the region. In the late-1800s, over 100 years of lumbering left the once abundant forests bare. The industry faded and the raftsmen left; their stories and songs stayed behind.

The raftsmen’s music did not disappear throughout the following century, but the song had been disassembled and dispersed—some were missing lyrics, some melodies, some were just fragments of what they’d been.

Curtis’ started her quest with the “be all, end all” source on the old Delaware lumber trade: Les Wood’s “Holt! T’other Way!” Derived from interviews with former raftsmen, the book lists the names of songs that they used to sing, but without lyrics or melodies.

She drew slightly closer with another book, “New York State Folk Lore, Legends and Ballads,” which included lyrics to some of the songs listed in Wood’s book. But it wasn’t until she discovered “Folk Songs of the Catskills,” which had both words and music, that Curtis was able to match the original list of songs with their respective words and melodies.

Through Curtis’s compilation, it’s immediately apparent what defined 19th century life in the Upper Delaware: work.

The first song in the compilation, “Cutting Down the Pines,” describes working in lumber.

Another popular song, “A Shantyman’s Life,” illustrates a bleak picture of life as a lumberman, or shantyman. ("Shanty” was another name for a bunkhouse where lumbermen dwelled.)

Work not only shaped the narratives of these songs, but the direction of their travels as well.

“As lumbermen worked in different places, they carried the songs with them,” Curtis said. “You might think of something as being a Delaware River song, but it may have turned up 100 years before in New England at a lumber camp.”

While songs are useful tools for identifying the region they’re from and the people who sang them, the melodies are transient creatures, moving freely through space and time, appearing in separate states, countries and continents—decades apart—their routes and modes of transportation unknown. From Curtis’s research, it’s clear that the “songs of the Upper Delaware” rarely originated there. Many of the tunes can be traced back to Ireland, Scotland and England, and the lyrical content implies the migratory lives of workers, who came to the Delaware singing songs about Texas Rangers, a “dying Californian” and the raftsmen of Flat River in Michigan.

Workers often reused melodies from existing folk songs, and reworked the words to make them more personal and relatable, Curtis said, noting that the melody of “The Star Spangled Banner” actually came from an old drinking song. “Cutting Down the Pines” is based on an older folk song, “The Bigler’s Crew,” and “A Shantyman’s Life” is set to the tune of “Barbara Allen,” a folk song that traces back to the 1600s. This malleability is why a region’s traditional folk music is beyond static definition, because it was constantly being redefined by those who sang it; it followed them through their journeys, evolving and shifting with the turbulent lives they led.

History may be written by the victors, but it is sung by the people. Antithetical to the style as it may be, the formal musicological term for folk songs—"vernacular music"—perhaps strikes nearest to the core of the genre’s vitality to understanding past cultures. Song was as important to a region as the vernacular language, in some ways a language unto itself. Beyond the stories contained within a song, tracking the story of the song—where it’s gone and how it’s changed— paints an alternate picture of the history.

“They were farmers, and they were lumberman and they were laborers,” Curtis said, describing the immigrants from mostly European countries such as England, Holland and Germany, who came to this region looking for work. “The people that brought these songs with them, they weren’t the folks that came here with a lot of money in their pockets.”

As a historian, Curtis has always gravitated toward viewing history through this lens of local lore and vernacular music. She sometimes refers to herself as “the historian who can’t remember dates,” because she understands the past through absorbing its culture, not by memorizing facts and figures.

“I am more interested in the lives that people led,” she said. “It puts things in perspective… They were real people like us, and they told funny stories, and they liked to listen and sing music.”

Curtis was present for a major turning point in the story of folk music, when singers like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez brought it back into popular culture in the ‘60s. The music that once accompanied laborers through a long day’s work now scored the movements of workers, marginalized people, women and anti-war activists.

Folk songs served a new purpose during this time, but the communal tradition of folk music stayed the same. A famous pro-union song “Which Side Are You On?” came from a traditional folk song “Jack Monroe.” One of the Civil Rights Movement’s key anthems, “We Shall Overcome,” derived from several different hymns and spirituals. Bob Dylan’s anti-war song “With God on Our Side” is set to the tune of the Irish rebel song “The Patriot Game.” (Click here to hear Pete Seeger's version of "Jam on Gerry's Rocks.")

“As a storyteller, I am deeply drawn to the interaction between folk music and storytelling, and how that feeds us as human beings,” Curtis said. “It’s history as I like to think of it… it’s our story,”

Curtis, whose family had lived in Sullivan County for 250 years, has since moved to Maryland. She still carries on the tradition of telling stories about the Delaware raftsmen, now to the other members of her retirement community.

“Even though most of them have never seen a hemlock tree or certainly the Upper Delaware Valley, they love the stories,” she said.

She knows of at least one folk singer who lives in her community, whom she hopes to bring the music to, and once again bring the songs of the raftsmen to life.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here